The new iPhone 17 and why we need (more than ever) a Secure and Independent Mobile OS

12 September 2025 • 22 min read

A Leap Forward in Cybersecurity

Apple’s latest iPhone release has brought good news for cybersecurity, thanks to significant new defenses against spyware and other cyber threats. Notably, the iPhone 17 lineup introduces a Memory Integrity Enforcement (MIE)feature that Apple calls “the most significant upgrade to memory safety in the history of consumer operating systems” . This always-on protection, built on ARM’s Enhanced Memory Tagging Extension (EMTE), covers the kernel and dozens of critical processes to block memory exploitation techniques commonly used by spyware like Pegasus . In practical terms, MIE assigns a secret tag (like a unique key) to each chunk of memory; if malicious code doesn’t have the right tag, the system prevents access, causing the attack to fail and log the attempt . This advance is expected to make life much harder for spyware developers. As one researcher observed, Apple’s new safeguards will “make their life arguably infinitely more difficult” , potentially raising the cost and complexity of developing spyware to the point of forcing some vendors out of the market . Experts predict that for a time, spyware makers may have no working exploits against the new iPhones – a testament to how seriously Apple is confronting threats like Pegasus .

Importantly, these defenses don’t only target remote spyware attacks. According to cybersecurity analysts, Apple’s MIE will reduce the effectiveness of both zero-click remote hacks (such as Pegasus or Paragon’s Graphite malware) and physical device hacks that use forensic tools like Cellebrite or GrayKey . In other words, the new iPhone’s security upgrades protect against a wide spectrum of attacks, from covert spyware injections to attempts at unlocking a stolen device. Apple can achieve this comprehensive approach in part because it controls its whole technology stack – custom hardware (the new A19 chip) and software – allowing deep integration of security features . (Google’s Android has begun adopting memory tagging on some devices, and the security-focused GrapheneOS project even enables it on Pixel phones, but experts note Apple’s end-to-end implementation puts the iPhone 17 among “the most secure mainstream” devices available .)

The iPhone’s new Memory Integrity Enforcement builds on Apple’s recent track record of strengthening iOS security in response to advanced threats. In 2022, Apple introduced Lockdown Mode as an optional “extreme” protection setting to counter spyware like Pegasus. When enabled, Lockdown Mode shuts off or restricts certain features (attachment types, web technologies, incoming invites, etc.) to dramatically reduce the device’s attack surface . This mode is intended for high-risk users (journalists, activists, diplomats, etc.), and early reports suggest it’s been effective: security researchers have found evidence that Lockdown Mode helped block real-world spyware attacks targeted at iPhones . In fact, Kaspersky’s analysts noted “several public reports on the success of Apple’s newly added Lockdown Mode in blocking iOS malware infection” . Beyond Lockdown Mode, Apple has continually hardened iOS with features like BlastDoor, an isolated service that safely processes iMessage content to thwart zero-click exploits, and hardware security elements (Secure Enclave processors for encryption and Face ID/Touch ID biometrics). The bottom line is that the new iPhone’s combination of hardware and software defenses represents a significant victory for user security – it raises the bar for attackers, especially the “mercenary spyware” industry that thrives on infiltrating smartphones . For users concerned about cyber surveillance, the iPhone 17’s advancements (from MIE to Apple’s strong patching practices) are very good news.

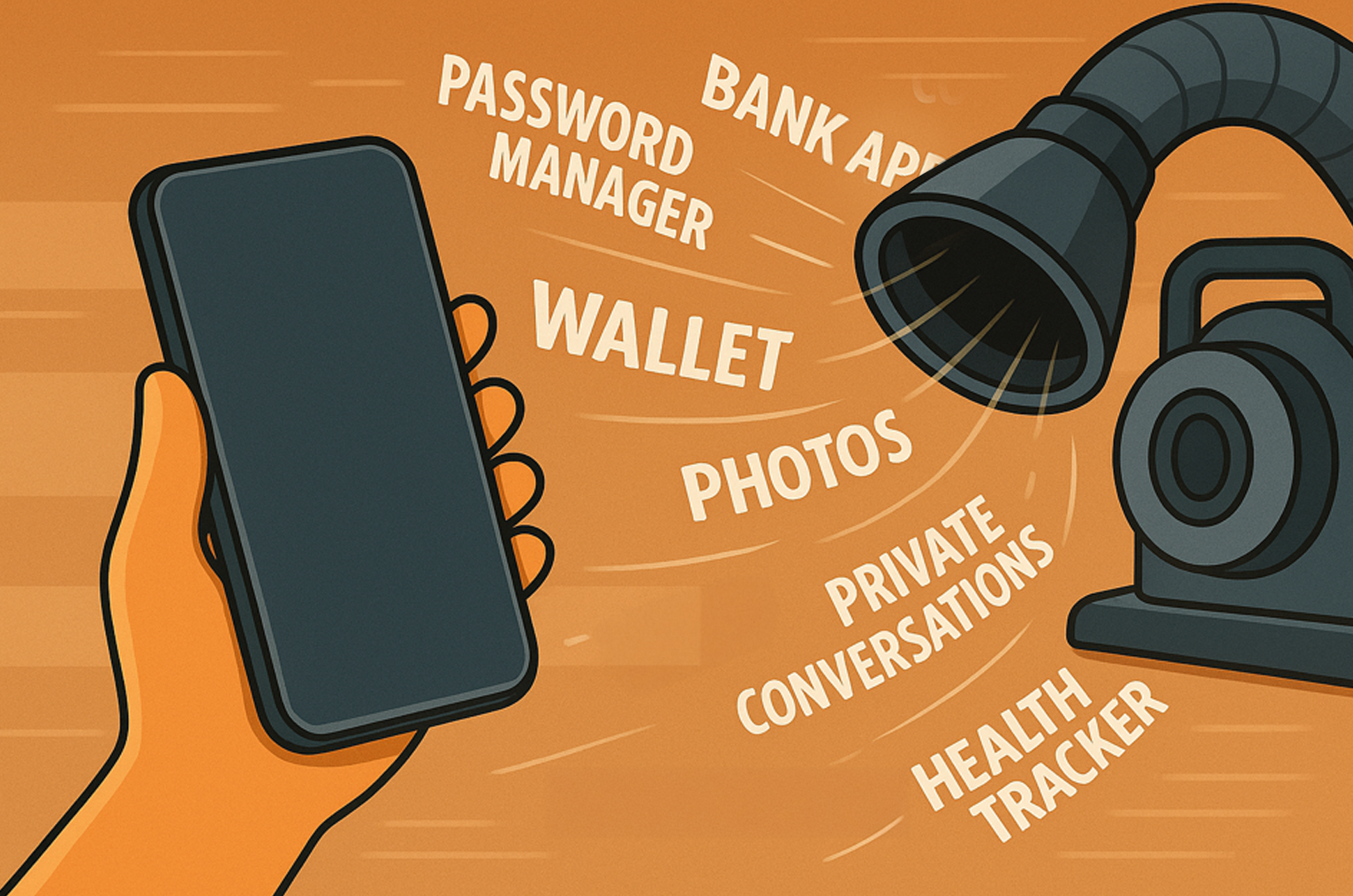

Smartphones: Our Most Sensitive Digital Assets

Why are these security improvements such a big deal? Because a modern smartphone isn’t just a phone – it’s your wallet, office, and safe deposit box all in one. Our mobile devices now hold an extraordinary amount of sensitive information and perform critical identity functions. Banking details, mobile payment apps, and cryptocurrency wallets; personal health records and medical apps; private chats, emails, and photos; constant location data; authentication apps and one-time passcodes for other accounts – all of these live on our phones. As a recent industry white paper put it, “Your smartphone holds more than just your photos and messages; it stores your banking details, personal health records, and access to crucial accounts” . Losing control of your phone, whether through theft or hacking, can therefore be catastrophic. It’s not just about the inconvenience of a lost device – it’s about protecting your digital identity and all the doors that a compromised phone could unlock . Attackers who infiltrate a phone might empty your financial accounts, impersonate you (identity theft), read your confidential communications, or even leverage the phone to breach other connected systems (for example, using a compromised phone’s VPN or authentication tokens to enter a corporate network).

Smartphones have effectively become keys to our kingdom of personal data, which is why they are high–value targets for cybercriminals and spies. This reality underscores a critical point: robust smartphone security is not a luxury, but a necessity. Apple’s efforts with the new iPhone highlight one approach – a tightly controlled ecosystem where the vendor heavily fortifies the device. Yet, even as Apple leads in security features, many users and experts are asking a deeper question: Is relying on a single vendor’s closed ecosystem enough to truly safeguard such a vital asset? The fact that so much of our life is concentrated in one device raises the stakes for transparency and trust in how that device is secured. This is why some voices in the tech community are calling for something more radical – a more open, independent mobile operating system that users (and the public) can inspect and trust, instead of having to accept opaque assurances from the big providers. In the next sections, we’ll explore this idea and why it’s gaining traction.

The Case for an Independent, Transparent Mobile OS

Today’s mobile OS market is effectively a duopoly: Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android dominate nearly all smartphones worldwide. While both have advanced security in many ways, they also present certain trade-offs and risks for users, particularly around privacy and control. Both Apple and Google are large corporations with their own agendas – Apple tightly controls its closed-source iOS platform, and Google’s Android, though based on open-source code, comes bundled with proprietary Google services that vacuum up data. As a result, users often have to sacrifice privacy or autonomy in exchange for convenience. “The duopoly that exists worldwide (Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android) makes it exceedingly difficult to find a mobile device that does not knowingly share one’s personal information,” notes one security-focused tech firm, adding that “forsaking privacy to tech titans… has been the norm” . In practice, a typical smartphone is very “leaky,” constantly collecting and transmitting data about your location, habits, and communications to parties like advertisers, data brokers, and the platform owners themselves . This happens through app trackers, cloud services, voice assistants, and countless other channels running in the background of iOS/Android. For high-security users such as government officials, journalists, or corporate leaders, this lack of control is more than an annoyance – it’s a serious security risk . Even regular consumers are increasingly worried about how much of their lives are in the hands of Apple, Google, and app developers.

The call for a more independent mobile OS stems from the desire for greater transparency, user control, and trustworthiness in our most critical devices. The idea is that an open-source or community-driven OS, not beholden to Big Tech, could be audited by anyone to ensure there are no backdoors or egregious data collection. Transparency is a key benefit – for example, Purism (a company developing an open mobile OS) points out that with a fully open-source system, “all the software running on the device can be audited and verified by the community, providing an additional layer of security” . In contrast, with proprietary systems like iOS (or heavily modified Android builds), users must simply trust the vendor since the source code and many system behaviors are closed off . A related benefit is customization and user sovereignty: an independent OS could allow users to choose exactly what services or apps run on their device, rather than being stuck with preloaded apps or hardwired settings that send data out. Advocates argue that such an OS would empower users to shape their phone’s security to their needs, much as one can with a PC running open-source Linux.

Another motivation is reducing reliance on a few corporations for security updates and policies. Regulators have noted that the mobile duopoly gives Apple and Google a “vice-like grip” on the market, limiting competition and choices for consumers . The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority warned in 2021 that these two companies not only dominate sales, but also “set all the rules – from determining which apps are available… to making it difficult to switch to alternative browsers” . This tight control could stifle innovation in security and privacy. If an independent OS were developed openly by a community or a coalition of organizations, its evolution would not be at the mercy of any single company’s business model. For instance, security fixes or privacy enhancements could be deployed based on technical merit and user interest, not delayed or denied due to a platform owner’s commercial priorities. Some governments are also keen on breaking this dependence; in India, for example, a state-backed project has created “BharOS,” an Android-based mobile OS intended to give users an alternative without Google’s surveillance . All of this underscores a growing need for diversity and openness in mobile operating systems – not just for the sake of competition, but for national security, privacy rights, and user safety. When smartphones are as critical as they are today, having only two corporate-controlled OS options is increasingly seen as a strategic and security liability.

Alternatives Beyond iOS and Android

Despite the dominance of Apple and Google, there do exist alternative mobile operating systems and modified versions of Android aimed at greater security/privacy. These projects remain niche, but they provide a glimpse of what a more independent mobile ecosystem could look like. Below is an overview of the different categories of alternatives and notable examples in each:

- Android-based “Custom ROMs” (De-Googled Android): A number of open-source projects build on the Android Open Source Project (AOSP) but strip out Google’s trackers and add privacy features. Because they still run the vast library of Android apps, these are among the most feasible options for everyday users seeking independence from Google. In fact, “options like Graphene and /e/ are more feasible, intuitive and functional than the defaults shipped by big OEMs,” according to one privacy lab founder . The GrapheneOS project is a leading example – a nonprofit, security-hardened Android distribution praised for its stability and robust defenses . GrapheneOS is designed for high-risk users (it was created by a security researcher) and eliminates entire classes of vulnerabilities through a hardened kernel, compiler, and memory allocator . Another is /e/ OS (Murena), started by a former Linux developer, which focuses on privacy for everyone – it comes pre-installed on some refurbished phones and aims to be easy to use out of the box . /e/ replaces Google services with its own privacy-respecting cloud services and has an app store that warns of trackers. CalyxOS is yet another AOSP-based OS that is geared towards privacy while maintaining usability; it integrates microG (an open replacement for Google Play services) to allow notifications and apps that rely on Google frameworks, but without Google’s data collection. LineageOS, and its fork Replicant, are community-driven Android distributions as well – LineageOS (successor to the old CyanogenMod) provides near-stock Android minus bloatware and supports a wide range of devices, while Replicant is a fully open source variant (even aiming to replace closed drivers where possible). These custom Android systems are appealing because they let users keep using familiar apps and device hardware, but they cut out the Google middleman and often come with improved privacy defaults. They demonstrate that we can have a smartphone OS that isn’t constantly siphoning data to Big Tech. However, they face challenges in matching the polish and seamless experience of official OS releases, and users must usually flash these ROMs onto devices themselves – a technical hurdle for many.

- Pure Open-Source Mobile OS (Linux-based): A more radical departure from the Android/iOS model are mobile OSes built on Linux, similar to a desktop Linux distribution, which are independent by design (not derived from Android). These include projects like PureOS/Librem, Ubuntu Touch, and Sailfish OS. For example, Purism’s PureOS (used in the Librem 5 phone) is a fully free/open-source GNU/Linux OS that emphasizes security and privacy at every level . Because it’s open, the code can be audited by anyone – “unlike iOS or even Android… where users must trust the companies without independent verification” . PureOS and the Librem devices also offer unique hardware protections like hardware kill switches (to physically disconnect the camera, mic, WiFi, etc.) and separation of cellular baseband from the main CPU for security . Similarly, Ubuntu Touch (now maintained by the UBports community) attempted to bring the popular Ubuntu Linux to phones, offering a convergent experience (a phone that could double as a desktop PC) and a truly Linux-based mobile environment. Sailfish OS, developed by Jolla, is another independent mobile OS (with a Linux core) that has been used in niche markets; it’s partially open source and notably can run Android apps through a compatibility layer. These Linux-based systems typically prioritize open development and privacy – for instance, they do not integrate any Google or Apple services, and they often use sandboxed app frameworks (like Flatpak on PureOS) to isolate apps. The trade-off, however, is a limited app ecosystem and sometimes a less smooth user experience. Without native support for the millions of Android/iOS apps, users may be confined to web apps or a small store of community-made apps. This makes daily adoption difficult for all but the most privacy-conscious enthusiasts. Furthermore, these projects have struggled with funding and hardware support – the Librem 5 phone, for example, is costly and had production delays, while Ubuntu Touch relies on volunteers and works on a short list of older devices (or specialized hardware like PinePhone). Still, they play a critical role as pathfinders for what a fully independent mobile OS can achieve in terms of transparency and user control.

Pros and Cons of Existing Alternative Solutions

To better understand the landscape, let’s look at some existing mobile OS alternatives and summarize their strengths and weaknesses:

- GrapheneOS:

- Pros: Extremely high security and privacy hardened – it adds exploit mitigations, stronger sandboxing, and a host of low-level improvements to Android . Ideal for high-risk users, it’s open source and does not include any Google services by default (though it lets you sandbox them if needed) . Offers Android app compatibility without the usual Google data mining, and gets timely updates.

- Cons: Limited device support (officially only Google Pixel phones, to take advantage of their security hardware and firmware). Installation requires some technical know-how (manual flashing). The out-of-the-box app selection is sparse (no Google Play Store, only a few apps like a hardened browser), so typical users must sideload apps or use alternative app stores. In short, it sacrifices some convenience for maximum security.

- CalyxOS:

- Pros: Focuses on privacy with usability – comes with features like encrypted backups and firewall, but unlike GrapheneOS, it includes microG services to support apps that rely on Google APIs (push notifications, maps, etc.) without full Google tracking. Has an easy installer and is backed by the non-profit Calyx Institute. Good for users who want better privacy than stock Android but still need mainstream apps to work smoothly.

- Cons: Not as aggressively hardened as GrapheneOS (the threat model is more about stopping trackers and hackers at large than nation-state level attacks). Officially supports mainly Pixel devices as well. Users may still need to be cautious with which apps they install, as app isolation is default Android level (though you can use the built-in VPN, Tor, etc. for more safety).

- /e/OS (Murena):

- Pros: Privacy-centric and user-friendly – targets average users who want to escape Google’s ecosystem. It removes Google code and trackers, and provides its own cloud synchronization service (for contacts, files, etc.) that is privacy-respecting. Offers a familiar Android experience (pre-loads an app store, email, maps, etc.) so you can use the phone normally without Google watching. They even sell Murena phones with /e/OS pre-installed for convenience . Has broad device support (many older models), extending the life of hardware.

- Cons: Security hardening is not as strong as GrapheneOS – it’s more focused on privacy (removing Google) than on resisting malware or exploits. Often lags a bit behind the latest Android version; some devices run older base versions which might mean slower security patches. Reliant on the small /e/ Foundation for updates and the smooth running of their cloud services. Essentially a great de-Googled experience, but not a high-security solution against advanced threats.

- LineageOS:

- Pros: Open-source Android with a huge community. It continues where CyanogenMod left off, providing clean Android for many devices that OEMs no longer update. It allows users to prolong the life of their phones with newer Android versions and has no built-in Google apps (users can choose to flash them or stay Google-free). LineageOS is quite stable and customizable, making it popular among enthusiasts.

- Cons: Being a community project, official support depends on volunteer maintainers for each model – some builds may not be fully stable. Installation requires unlocking the bootloader (which can weaken the device’s built-in security and void warranties). Lacks the specialized security enhancements of GrapheneOS or the integrated services of /e/, so users must tweak privacy settings on their own. Also, without Google apps included, a user must decide whether to sideload an open app store (like F-Droid) or manually add Google packages (defeating the de-Googling goal). Essentially, LineageOS offers openness and longevity, but not a turnkey secure/private setup by itself.

- PureOS / Librem 5 (Linux OS):

- Pros: Fully auditable and transparent system – built on pure Debian GNU/Linux. Emphasizes security by design (no proprietary blobs in the OS) and includes powerful privacy features like hardware kill switches for camera, mic, radios . Because it’s essentially Linux, advanced users can run standard Linux software and have complete control over the device. There’s no Big Tech oversight at all: no Google, no Apple, and no data harvesting – the manufacturer (Purism) doesn’t monetize user data . Suited for those who need absolute trust and customization, such as some government and military users who require open verification of their device security .

- Cons: The Librem 5 phone hardware is specialized and not as sleek or power-efficient as typical iPhones/Android phones. The OS, while robust, cannot run Android or iOS apps out of the box, which means the app selection is severely limited (though web apps and community Linux apps exist). General performance and battery life are behind mainstream smartphones, given the trade-offs made for openness. It’s also expensive due to low production scale. In short, this solution maximizes freedom and security auditability, but at the cost of mainstream app support and some user convenience.

- Sailfish OS:

- Pros: A unique independent OS with a polished interface and some commercial backing. It’s known for its smooth gesture-based UI and has been used in governmental and enterprise settings that seek an alternative to American OSes. Sailfish can run many Android apps (via a built-in compatibility layer), which eases the transition for users. The OS is less tied to Google/Apple services, giving users more control over data. Jolla (the company) has kept it alive through licensing (e.g. a Russian variant called Aurora OS was used for official government devices), showing it’s considered a viable sovereign OS in certain contexts.

- Cons: Not fully open source (some components like the UI are proprietary), which means it’s not as transparently secure as a Linux-based OS could be. Device compatibility is limited – officially it works on a handful of Sony Xperia models and Jolla’s own phone/tablet, with community ports for others. The Android compatibility is a generation behind (supporting apps up to a certain Android version), and the ecosystem of native Sailfish apps is small. Without wide adoption, updates and support rely on Jolla’s fortunes, which have been up and down. Overall, Sailfish OS offers a middle path (an independent OS with some Android app support), but it remains a niche player.

Each of these alternatives has its pros and cons, as we see. The common thread is that no single solution yet strikes the perfect balance of security, privacy, usability, and broad app compatibility to truly challenge iOS/Android head-on. GrapheneOS, for instance, is highly secure but not geared for mass adoption; /e/OS is user-friendly but not cutting-edge in security; Linux-based phones are open and transparent but lack apps and polish. This is not a criticism – it simply reflects how difficult it is to build a mobile OS (hardware + software + app ecosystem) from scratch or even from Android’s bones, without the massive resources of Apple or Google. It also highlights why Apple and Google remain dominant. However, these projects are trailblazing the path towards a more open mobile future. They prove that many users do want alternatives – in fact, consumer surveys and communities show people are “seeking innovative, more secure, and more private alternatives to the Google and Apple smartphone duopoly” . The interest is there, even if the solutions are still maturing.

Toward a Secure and Transparent Mobile Future

The new iPhone’s security enhancements and the emergence of alternative OS projects together paint an interesting picture of our mobile future. On one hand, Apple’s approach demonstrates the benefits of vertical integration – by controlling chip design, operating system, and update pipeline, Apple can roll out game-changing security features (like MIE) relatively quickly and protect hundreds of millions of users. On the other hand, the need for an independent mobile OS underscores something just as important: user trust and freedom. The ideal scenario for users would be to have both: devices that are extremely secure and operating systems that are open and transparent. We may ask, how can we achieve this combination?

One possibility is a community-driven mobile OS initiative supported by a broad alliance of stakeholders. This could involve open-source developers, privacy organizations, academic experts, and even enlightened government agencies pooling efforts to create a truly open, secure mobile platform – much like Linux was developed and is maintained for servers and desktops. If the tech industry and governments recognize smartphones as part of critical infrastructure (holding personal and even national secrets), they might invest in such a collaborative project. A community solution would prioritize security and privacy as design goals rather than ad-driven revenue or lock-in, and it would invite public audit of its code. The challenge, of course, is how to catch up to the incumbents. Any new OS needs more than code – it needs device hardware to run on and an app ecosystem. This could be jump-started by, say, adopting Android compatibility (like Aurora/Sailfish or even using AOSP as a base but under strict community governance) so that users can run essential apps securely while a native app ecosystem grows. We’re already seeing steps in this direction: GrapheneOS’s developers have contributed many of their improvements back to the Android open-source project, benefiting billions of devices , and organizations like the Linux Foundation might one day rally companies to support an open mobile platform as a public good.

It’s worth noting that even regulators are pushing to loosen the duopoly’s grip – for example, authorities are mandating interoperability and sideloading (allowing alternative app stores on iOS, for instance) which could lower barriers for third-party OS or software distribution . Such policies could make it easier for an independent OS to gain traction, since users could switch without losing all their apps or data . In the long run, security and transparency go hand in hand. The more eyes on the code and the more diversity in the ecosystem, the harder it is for a single flaw or backdoor to compromise millions of devices. A monoculture (where everyone runs either iOS or Google Android) means a single exploit can have universal impact – something spyware makers have certainly taken advantage of. A diverse set of trusted OS options would act like biological diversity, containing damage and catering to different threat models.

In conclusion, the latest iPhone shows that strong security is achievable on consumer devices – a win for users against cybercriminals. But it also reminds us that relying on proprietary solutions from a handful of companies has its limits. As our smartphones become ever more central to our lives, the push for an open, auditable, and independent mobile OS will likely intensify. The goal is to reach a point where users don’t have to choose between top-notch security and trusting a black-box ecosystem – instead, they could have a device that is both highly secure and whose software is transparent and community-vetted. Getting there won’t be easy, but the stakes are high: our privacy, our data, and our digital freedom in an increasingly connected world. The conversation between Apple’s advancements and the independent OS movement is a healthy one, and ultimately, users stand to benefit from the improvements and choices that emerge. As one expert aptly said, consumers are now looking for true choice beyond the big two, seeking solutions that *“guarantee user sovereignty, robust security, and complete control” over their mobile companions . The coming years will show how close we can get to that ideal.